Amendment Twenty-one to the Constitution was ratified on December 5, 1933. It repealed the previous Eighteenth Amendment which had established a nationwide ban on the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol. The official text is as follows:

The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.

The transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or Possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.

This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by conventions in the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.

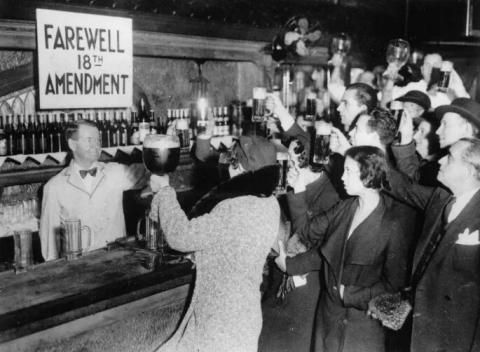

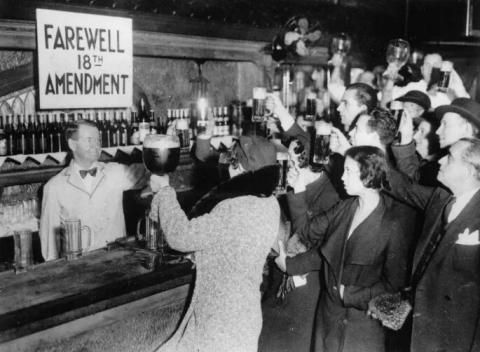

In 1919, under federal enforcement from the Volstead Act, the Eighteenth Amendment imposed a nationwide prohibition on alcohol. While many Americans still drank alcoholic beverages since the new laws did not forbid the outright consumption of them, an underground market formed in the wake of the Amendment’s passage. The immediate impact of prohibition appeared to be positive in the first few years of the 1920s, with an overall decline in crimes that the temperance organizations considered to be rooted in alcohol consumption. As the decade continued however, illegal alcohol production increased to compensate for the increasing demand for it. The prices for these illicit beverages, which had skyrocketed at the beginning of Prohibition, had gone down by the increasing underground alcohol producers. Additionally, the illegal alcohol production centers grew ties with organized crime organizations, such as the Chicago Outfit under the leadership of mob boss Al Capone. The increasing influence of these criminal organizations allowed them to bribe businesses, political leaders, and entire police departments with the illegal alcohol, effectively crippling the ability to enforce the Eighteenth Amendment. By the 1930s, overall public sentiment toward prohibition had diametrically flipped from positive to negative, and Congress was compelled to act accordingly.

On February 20, 1933, Congress both initiated the Blane Act and proposed a new amendment to end prohibition. For the first time in the history of the Constitution, the new amendment was sent out for ratification by state ratifying conventions, as opposed to the more frequent method of state legislatures doing so. The proposed amendment was ratified on December 5, 1933, whereupon Secretary of State William Philips certified the three-fourths requirement being reached. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a proclamation regarding the new Twenty-first Amendment, confiding his trust in the American people that they would “not bring upon themselves the curse of excessive use of intoxicating liquors to the detriment of health, morals, and social integrity.” While the ban on alcohol was lifted by the Twenty-first Amendment, Section 2 implies that the states are ultimately in charge of regulating the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol. This was to account for certain states that were more in favor of the prohibition laws than others, allowing them time to decide if they wanted to lift the bans. Ultimately, Mississippi was the last state to lift all its Prohibition-era laws in 1966, while Kansas lifted its ban on public bars in 1987. In the decades since the Twenty-first Amendment, a series of Supreme Court decisions have been argued and ruled over, specifically regarding Section 2. Certain states have argued in favor of their implied authority to regulate the transportation of certain types of alcoholic beverages under the Commerce Clause and the Dormant Commerce Clause. The rulings have set general guidelines regarding the limitations of advertising beverages and their prices, and allowed percentages in certain counties and municipalities within states. The Twenty-first Amendment is unique both in the way it was ratified, and its ultimate purpose to repeal a previous addition to the Constitution. From a historical perspective, the amendment works as a bookend of a unique segment of early 20th century American history.